North Stars:

Wildlife Ecosystems

Carbon Footprint

Community Support

“Our guests enable the scientific research that takes place here in our reserve.”

Aerial view of Mashpi Lodge. Courtesy of Mashpi Lodge.

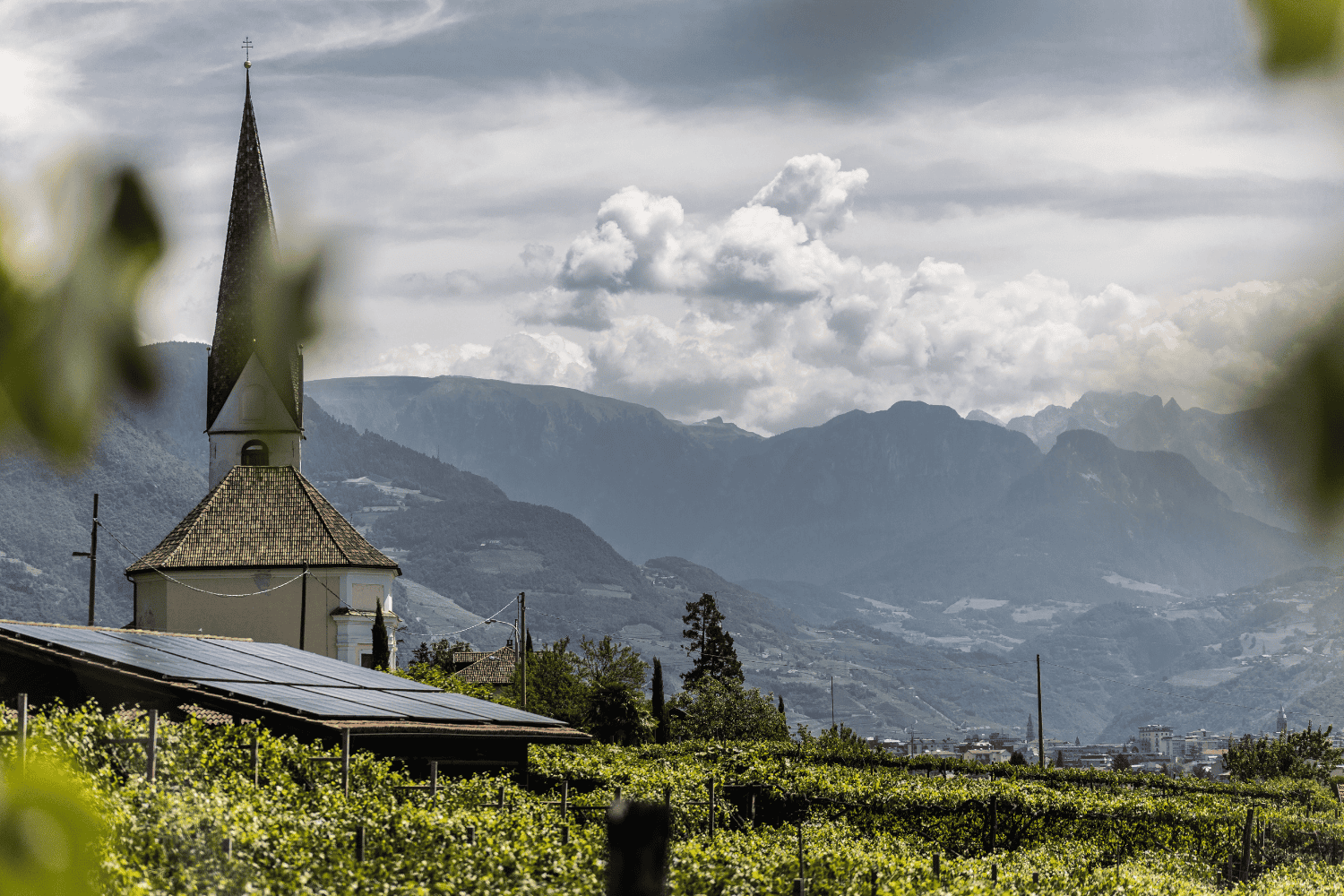

After checking in at Ecuador’s Mashpi Lodge, guests step outside to watch a drone rise above the canopy. The footage, given as a souvenir, shows the lodge shrinking to a silver speck in a vast expanse of green. It’s a striking reminder of how completely the rainforest surrounds this place and of what the lodge exists to protect.

Mashpi Lodge sits inside a 7,400-acre reserve in the Chocó and Tropical Andes ecoregions, about three and a half hours northwest of Quito. The area is part of the Chocó Bioregion, one of the planet’s biodiversity hotspots, with hundreds of endemic plant and animal species. Built with responsible practices in mind, the lodge’s design makes the forest the focus. Floor-to-ceiling windows open onto a wall of foliage. Trails lead straight from guest rooms into dense vegetation. Waterfalls and rivers cut through the valley below.

For most visitors, the draw is access to a remote ecosystem. But Mashpi isn’t only a place to observe nature. It funds the science that helps protect it.

Inside the Mashpi Research Lab. Courtesy of Mashpi Lodge.

Holiday in the Heart of the Jungle

Designed by Ecuadorian architect Enrique Muñoz, Mashpi Lodge is built from steel, glass, and stone along a former logging road, a site chosen to minimize the build’s environmental impact. The structure feels modern but unobtrusive, perched on a ridge that overlooks dense valleys.

Inside, the polished modern aesthetic makes use of local materials like wood and volcanic stone, while incorporating soft, neutral fabrics that mirror the colors of the forest. The design blurs the line between interior and exterior; every space faces the rainforest. At night, the glass reflects the moonlight while the sounds of insects replace the usual din of city life.

Meals follow that same philosophy of integration. The dining room spans two levels with a glass-walled design that places the rainforest on view from every table. Emphasizing Ecuadorian flavors set against international technique, the restaurant’s menu from chef Luis Cárdenas reflects the lodge’s location serving dishes from Andean potato soups to fish prepared in banana leaf, a nod to coastal traditions. Even cocktails reflect the region’s tropical fruits and spice flavors. As for sourcing, many of the ingredients come from nearby farms and local collectives, part of Mashpi’s effort to support sustainable livelihoods at the forest’s edge.

Mashpi Glass Frog. Courtesy of Carlos Morochz.

Science in the Forest

Mashpi Lodge operates as both hotel and field station. Alongside the guest areas, it hosts a research lab and a Life Center with a butterfly farm where scientists, researchers, and local parabiologists study the surrounding cloud forest. Since the lodge opened in 2012, 24 species have been formally described within the reserve, including the Mashpi glass frog, the Mashpi magnolia, and the Mashpi tiger ant.

To date, Mashpi’s collaborations have produced 36 scientific papers, more than 120,000 camera-trap images, and extensive biodiversity records: 716 plant species, 410 birds, 118 amphibians and reptiles, 96 mammals, 25 fish, and more than 500 butterflies and other invertebrates.

These discoveries aren’t made in isolation. The lodge partners with Ecuadorian and international universities to document biodiversity, track wildlife populations, and monitor climate impacts. Researchers now have consistent access, equipment, and long-term funding — a rare advantage in tropical research. The reserve also welcomes undergraduate and graduate students who conduct field studies to expand knowledge of this under-documented ecosystem.

For guests, that science is part of the experience. Guided hikes lead to waterfalls, canopy platforms, and observation towers where naturalist guides explain current studies in real time. The Sky Bike lets visitors pedal across the understory, and the Dragonfly cable car glides through the canopy, offering a view of the ecosystem. Back at the lodge, evening talks by the research team translate field observations into stories about behavior, habitat, and species interactions.

“Our guests enable the scientific research that takes place here in our reserve,” says hotel manager Alex Veintimilla. “They have a direct impact on improving knowledge about this biodiverse, yet little-studied ecosystem.”

Mashpi Magnolia. Courtesy of Mashpi Lodge.

Conservation and Community

Mashpi’s story began in 2001, when Ecuadorian environmentalist and entrepreneur Roque Sevilla bought 1,730 acres of threatened forest to protect it from logging. The reserve has since grown to more than 7,400 acres. Today, the lodge employs hundreds of people from nearby communities and invests in local training programs that teach guiding, hospitality, and research skills.

“The lodge funds the research projects directly,” says Mateo Roldán, research and biology director. “The team started with one person in 2009, and now there are six people solely focused on research and conservation.”

Many staff members are from neighboring villages and have become integral to Mashpi’s scientific work. Former guides now collect data, maintain camera traps, and assist visiting researchers. Community projects in the area focus on sustainable agriculture and small-scale tourism that reduce pressure on the forest.

Expanding the Model

Mashpi’s conservation approach has influenced other nature-based initiatives. A partnership with French fragrance company MANE and The Red List Project, which works to protect endangered plants, recreated the scent of the Mashpi magnolia for the lodge’s bath products. A portion of the proceeds funds seedling nurseries and reforestation within the reserve.

Mashpi was designed from the start to connect science, conservation, and hospitality. “That focus was established before the lodge opened, not tacked on after it reached its break-even point,” says Veintimilla.

Metropolitan Touring, the company that manages Mashpi Lodge, applies the same model to its hotels and expedition ships in Quito and the Galápagos Islands. Sales of Mashpi’s bath products and other amenities help support long-term conservation programs across its properties.

Roldán says the goal is practical as much as philosophical. “Science should help people understand and connect better with nature,” he says. “It’s the ethos of our founder, Roque Sevilla, who wants Mashpi to be an example of how passion, knowledge, and hard work can fulfill dreams and change people’s lives in a positive way.”

By the time guests leave, they are no longer just visitors. Having glimpsed the hidden life of the reserve, they become informal ambassadors for its preservation.

If You Go

Getting There: Fly into Quito, then drive 3.5 to 4.5 hours to Mashpi Lodge. Guests can rent cars or book direct transfers from the city, which are included with reservations made through the lodge.

Know Before You Go: Rates include guided excursions, meals, and transfers from Quito. Bring waterproof shoes and lightweight rain gear. The lodge provides binoculars, field guides, and rubber boots for hikes.

Jill K. Robinson is an independent journalist who has written and contributed to several books, and contributes to a wide variety of print and digital publications, including National Geographic, AFAR, Condé Nast Traveler, and Travel + Leisure. She has received four Lowell Thomas awards from the Society of American Travel Writers Foundation, including the 2024 Silver Award for Travel Journalist of the Year. Follow her on Bluesky @dangerjr.bsky.social

North Stars: Carbon Footprint, Community Support, Wildlife Ecosystems