North Stars:

Heritage Value

Production & Consumption

Gender Equality

“Mann still climbs trees during a two-week window each year to harvest Western white pine cones.”

Inside the tasting room at Up North Distillery. Courtesy of Heide Brandes.

The Azure Road Take

The first sip of North Idaho Pine Liqueur hits your palate like a revelation. Sitting in Up North Distillery‘s tasting room on a cool May evening in Post Falls, Idaho, I braced myself for something harsh and medicinal. Instead, the clear spirit delivered a surprisingly smooth, complex flavor profile that tasted like the essence of the northwestern wilderness itself. It was unlike anything I’d experienced before, earthy yet refined, with the bright tartness of pine needles giving way to subtle honey sweetness.

Next came their signature honey spirit, crystal clear and impossibly smooth. One taste, and I knew my father, a devoted tequila lover, would be smitten. This wasn’t whiskey pretending to be something else. It was something entirely new, with agave-like qualities that could easily substitute for tequila in cocktails.

What I was experiencing was the result of Randy and Hilary Mann’s bold experiment in returning to mead, humanity’s oldest fermented beverage, and transforming it into complex, barrel-aged spirits that rival traditional whiskeys. Up North Distillery stands as one of only six distilleries nationwide that manufactures spirits using 100% honey in the mash, pioneering what industry experts believe could be the next major category in American craft spirits.

One of Up North's bottles of honey-based spirits. Courtesy of Up North Distillery.

Sustainability Chops

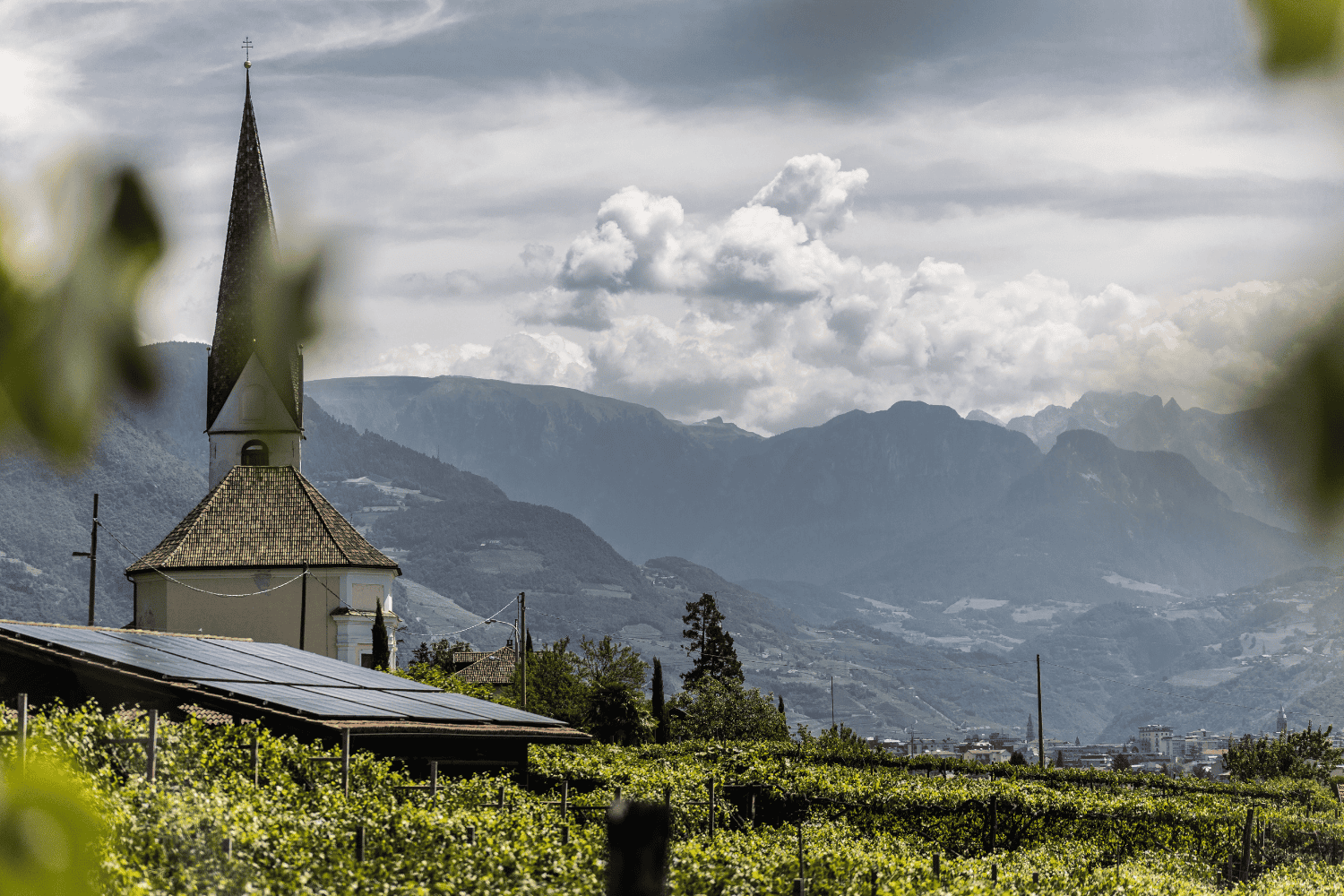

Up North’s commitment to local terroir goes beyond sourcing honey from Idaho producers. For their most distinctive product, North Idaho Pine Liqueur, Randy Mann still climbs trees himself during a narrow two-week window each year to harvest Western white pine cones, grown from Idaho’s state tree.

“There’s only about a two-week window when the pine cones are purple and full of sap before they open,” Hilary said. “He climbs the trees, shakes them off, and then brings them back to our distillery and soaks them in our apple brandy.”

This foraging expedition takes Mann to his favorite spots along the Coeur d’Alene River, and the timing is critical. Too early, and the cones lack sufficient sap. Too late, and they’ve opened and lost their concentrated pine essence. The pine liqueur represents a distinctly American interpretation of European zirbenschnaps, traditionally made with Austrian Arolla pine.

“Species of pine trees are so close, there are barely any real differences,” Mann said, emphasizing the similarities between Idaho’s pines and the European varieties.

To strengthen the liqueur’s local identity, Mann uses apple brandy distilled from northwest Idaho apples as the base spirit, rather than the corn-based neutral spirit typically used in European versions. Idaho honey provides the sweetener, creating a product that captures the essence of northern Idaho’s wilderness in liquid form.

The Sip

Unlike traditional distilleries that work with grain-based washes, Up North begins with honey sourced from southeastern Idaho. The process starts with fermenting mead, essentially honey wine, which requires a lengthy three-week fermentation period compared to the typical three-day process for grain-based spirits.

The extended fermentation allows natural enzymes and wild yeasts to develop complex flavor compounds that carry through distillation. Randy Mann distills the mead using traditional copper pot stills, then either bottles it clear or ages it in American oak barrels.

The industry has few rules when it comes to honey. This regulatory vacuum allows the Manns all the creative freedom they want. They can age in new oak, used oak, or skip barrel aging entirely. They’re not bound by minimum age requirements or specific production methods that govern whiskey, bourbon, and rye.

That freedom to experiment is paying off with a loyal following and respect from the distillery world. Professional tasters characterize the honey spirits as having a “sticky honey immediately present on the nose,” complemented by “fresh orange juice and wildflowers,” which contribute to the bouquet’s complexity.

Up North Distillery's tasting room. Courtesy of Heide Brandes.

Origin Story

Randy Mann was a power company lineman for most of his career until an injury derailed him. Seeking a career easier on his body, Mann turned to one of his hobbies: home brewing. After attending a class at the American Distillery Institute in Seattle, he returned to Idaho convinced he could transform his hobby into a livelihood.

“He came back and said, ‘Okay, I think we can do this,’ and talked me into it,” said Hilary Mann, who co-owns the distillery with her husband.

The honey component arrived serendipitously. While sourcing equipment, the Manns found a Montana distillery for sale that included a substantial honey supply. The previous owner, who had operated an apple orchard, also experimented with honey spirits.

“He told us, ‘You have to take this honey. It’s the same price with or without the honey,” Hilary said. “So we started experimenting with the honey and loved it.”

That accidental acquisition launched Up North into a whole new territory in American spirits production. The distillery began operations in October 2010 and opened to the public in 2015.

Despite entering an established market with unconventional products, Up North has garnered significant recognition, winning numerous awards and accolades.

The accolades were given not just for quality but for the industry’s growing interest in alternative base ingredients. As consumer palates become more adventurous and bartenders seek distinctive ingredients for craft cocktails, honey spirits offer a sweet alternative to traditional categories.

“It’s quite affirming,” Randy said of the awards. “It makes you feel like, ‘Well, I don’t really need to change what I’m doing.’”

As the craft spirits industry matures, Up North’s position as a category pioneer becomes increasingly valuable. The recent federal recognition of American single malt whiskey as a protected category validates its decade-long commitment to alternative approaches in American spirits production. While their single malt whiskey benefits from this regulatory clarity, their honey spirits remain in uncharted territory, exactly where the Manns prefer to operate.

“The honey spirits don’t fall under that umbrella at all,” Hilary said. “And there are actually no rules of identity for honey because it’s so unique, and not very many people are doing it.”

Heide Brandes is an award-winning journalist whose’ work appeared in National Geographic Traveler, The Wall Street Journal, The Smithsonian, Cowboys & Indians, Southern Living, Fodors, BBC Travel, ROVA, Outdoor x 4 Magazine and The Washington Post, and others. When not traveling and writing, Heide is an avid hiker, a medieval recreation enthusiast, a professional belly dancer and kind of a quirky chick from Oklahoma. Follow Heide on IG @heidewrite.

North Stars: Gender Equality, Heritage Value, Production & Consumption