North Stars:

Community Support

Energy Efficiency

Waste Management

“That consistency in people brings consistency in the product, shaping wines that remain true, year after year, season after season.”

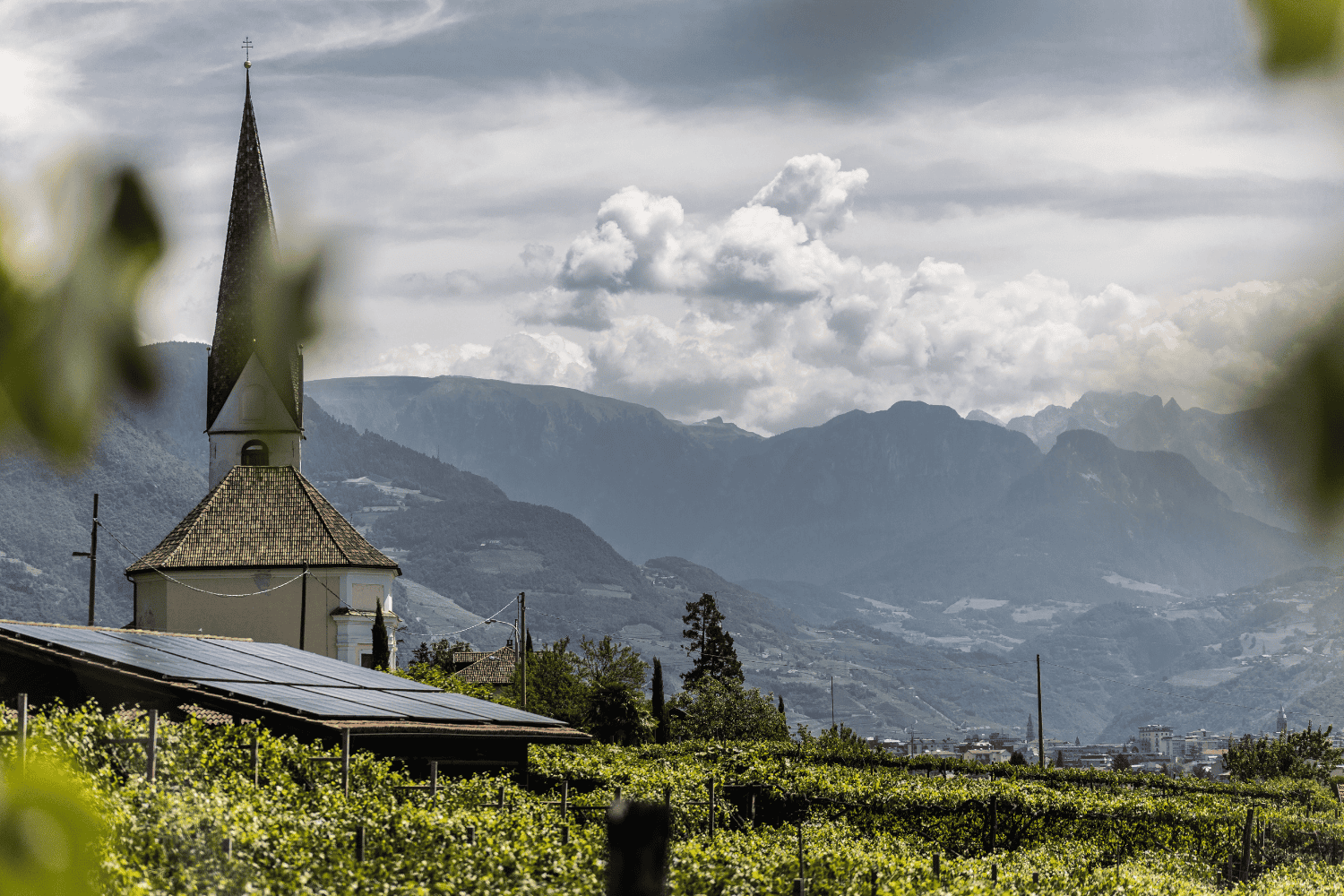

Wairau River's Vineyard at Dusk. Courtesy of Wairau River.

In New Zealand’s Marlborough wine region, scale often dominates the conversation. It’s the country’s largest wine-producing area by far, with sprawling vineyards and brands that ship Sauvignon Blanc around the globe. But at Wairau River, one of the early players in this now-iconic region, the story has always been different.

The winery was founded in 1978 by Phil and Chris Rose, pioneers who saw promise in the Wairau Valley when it was still mostly pasture and sheep paddocks. At the time, the couple was farming lucerne (alfalfa) for export to Japan. When the oil shock of the 1970s made drying and harvesting uneconomic, they looked for alternatives and fought through local resistance to plant vines. In true pioneering fashion, they hand-planted vineyards while raising a family. After years of contract growing, they released their first wines under the Wairau River label in 1991 to critical acclaim.

Today, Marlborough is home to over 500 growers and more than 150 wineries. While the region has expanded rapidly — both in production and profile — Wairau River has taken a different path. It remains family-owned, making wine entirely from estate-grown fruit. The Rose family now farms 1,412 acres across 14 vineyards, all in the Wairau Valley. The soils here are shallow and stony, free-draining and low in fertility, which naturally limits yields and promotes concentration. Protected from sea winds and fed by artesian water, these vineyards are considered among the plain’s most desirable sites.

Many of the people behind the wines have worked side by side for decades, from CEO Lindsay Parkinson, who has guided the business with a steady focus on quality and long-term thinking, to winemaker Nick Entwistle and viticulturalist Hamish Rose. In fact, in an industry shaped by international investment and frequent turnover, that level of stability is unusual. “That consistency in people brings consistency in the product,” says Rose.

The Rose family all together on the property. Courtesy of Wairau River.

A Vineyard-First Philosophy That Starts With Instinct

Wairau River farms all of its land in-house, an approach that gives the team immediate decision-making control—when to pick, how to farm, what to adjust — without relying on outside growers.

“You can’t control the weather,” said Entwistle, who joined in 2002. “But you can show up, work the land, and adapt when things get weird.”

The region’s dry, sunny climate offers some reliability, but each vintage still has its own personality. Grapes are picked by taste and intuition, not just by numbers. In the cellar, the approach is deliberately hands-off, aimed at preserving the character of the fruit.

“You can’t really teach instinct,” Nick said. “It comes from repetition,” he says, “and that means walking the rows year after year and noticing the small shifts.”

That direct connection between land and wine is one reason the bottles taste consistent year after year, even as the seasons change.

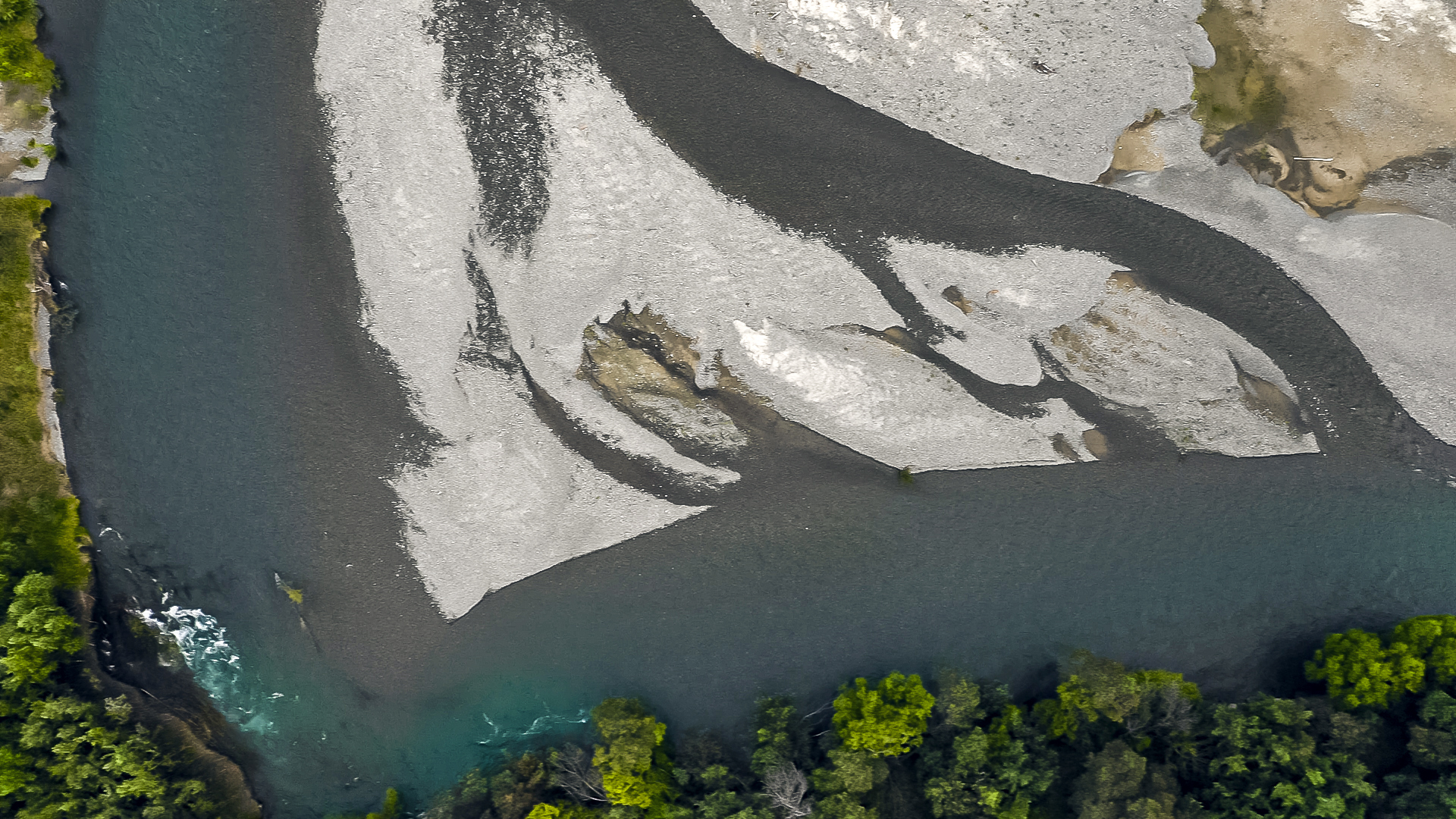

Aerial view of Wairau River. Courtesy of Wairau River.

Why the Best Winemakers Think Like Outdoorsmen

Spend time with the Wairau River crew, and it’s clear this is a team as comfortable outside the winery as in it. Nick grew up in Nelson on the South Island and worked in biotech before becoming a winemaker. He jokes that his fishing trips are “research,” but says time outdoors sharpens observation skills.

Rose, son of the founders of Wairau River, once worked as a pāua diver off the Kaikōura coast. Others on the small team hunt, hike, or head to the ocean and mountains in their downtime. That lifestyle reinforces an ability to read conditions, adapt quickly, and make decisions based on what’s happening in the moment; skills that are essential in farming and winemaking.

Unlike larger operations that often rely on contract fruit and seasonal crews, Wairau River’s grapes are grown, harvested, and fermented by the same people. That direct involvement from vine to bottle helps ensure the style and quality remain true to the estate.

Plunging Pinot Noir grapes. Courtesy of Wairau River.

Making Great Wine the Same Way for 40 Years—and Why It Still Works

Wairau River hasn’t built its reputation by chasing trends. Instead, it has refined its approach over decades, staying focused on the varieties and styles it knows best. Sauvignon Blanc remains the flagship, a wine that first won national recognition in 1991 and continues to define Marlborough’s identity today. Its vibrant acidity and lifted tropical fruit notes helped put New Zealand on the world stage.

But the family’s portfolio extends well beyond. Pinot Noir from northern Wairau sites shows lifted cherry and spice layered with subtle tannins, while Pinot Gris delivers textured stone fruit and honeyed notes balanced by natural acidity. Each wine reflects the same principles: harvest in the cool hours, handle fruit gently, ferment in stainless steel or French oak with minimal intervention, and let the vineyard character lead.

Wairau River’s connection to place runs deeper than winemaking. The name itself, meaning “many waters” in Māori, refers to the braided nature of the river that sustains the valley. The family’s bold label design, inspired by the river’s stratification, underscores that tie to the land.

Sustainability is woven into every decision. All vineyards and winemaking facilities are SWNZ-certified, ensuring best practices from grape to glass. As Lindsay Parkinson puts it, “Our family’s living is dependent on the land, and decision making has always been grounded in our responsibilities to both land and people.” For the Roses, this stewardship isn’t a marketing line, but rather it’s how three generations have built both a livelihood and a legacy.

Despite rising industry costs, the Wairau River continues to deliver strong value in the category. And for all the talk of terroir, it’s the people who have worked together for most of their careers who shape what ends up in the glass.

“You’ve got to let the vineyard speak,” Nick said. “Our job is to listen. And not mess it up.”

North Stars: Community Support, Energy Efficiency, Waste Management